Who really participates in engineering design reviews?

Who really participates in engineering design reviews?

Key Takeaways

.svg)

Design review is a loaded term.

Requirements review, cross-functional review, DFM review, test readiness review. Broadly, these mean something to engineering teams, but rarely do they mean the same thing across engineering teams.

And forget about what a “DFM Review” might mean from one company to the next.

This means it’s difficult to standardize design review across teams and external collaborators.

Because this standardization is difficult, it’s also difficult for engineering teams to know when to bring in:

- Other engineering teams

- Cross-functional teams

- Suppliers

- Customers

And because they don’t know when to bring in certain reviewers or the process for bringing in them in, participation from these groups drops. Worse, the perception that other engineers, suppliers, customers or cross-functional teams provide useful feedback during reviews also plummets.

This report will dig into the results from a survey of 250 engineering leaders when asked the question: How many members from each group participate and provide useful feedback during design reviews?

Not all your engineers provide useful feedback during design reviews – and you know it

Thankfully, engineering leaders believe some portion of their engineers participate and provide useful feedback during design reviews.

The more troubling statistics is that only 56% of engineering leaders believe most or all of their team provides useful feedback during design review.

Knowing what we know about the way teams conduct design reviews, this isn’t that surprising.

Most engineering teams use some combination of the following to facilitate design review and track the issues coming out of it:

- Meetings

- Spreadsheets

- PowerPoint

Let’s go a step further and dig into what the exact process for highlighting and resolving a single issue looks something like for most engineering teams:

- Engineer receives a PowerPoint deck with CAD screenshots to their email.

- Engineer marks up any potential issues on each slide.

- If they don’t understand the design intent and want to interrogate one section of the model further, they need to ask the design engineer to add another screenshot slide. Or, they just ignore it.

- Engineer sends the PowerPoint deck back to the design engineer.

- Design engineer makes the required changes, puts those changes into another deck and sends it back via email for review.

This process is a nightmare for engineers. Engineers got into engineering to solve big problems and make interesting, life-changing products. We often hear, “I didn’t get this degree to be a PowerPoint engineer.”

But this process boxes engineers in. So, what happens? They’re de-motivated by the unnecessary rigamarole of design reviews, so they choose not to participate – knowing they can solve the problem when it becomes that, a problem.

It’s not the fault, then, of the engineer that they don’t fully participate in design reviews, it’s the breakdown of the design review process.

Where cross-functional team participation succeeds – and where it breaks down

It seems intuitive for engineering to engage teams like manufacturing, quality, tooling and procurement during design reviews.

After all, these teams have valuable expertise that engineering doesn’t have. The data proves this out to a certain extent. Nearly half of all engineering leaders confirm that all or most of their cross-functional teams participate in design reviews and provide useful feedback.

Engineering teams that do this well tend to:

- Involve the right cross-functional teams. Sending an early model to procurement for an RFQ might not be appropriate. However, sending an early model to tooling to see if a critical part can be machined makes a lot of sense.

- Include cross-functional teams at the right time. Often, CAD is immature in the early stages, so involving manufacturing might add unnecessary complexity and confusion. However, bringing in quality engineering or a tooling engineer might be a requirement.

- Give cross-functional teams access to the right files. Giving procurement a CAD model to engage a supplier in an RFQ might be excessive. However, providing PMI or a drawing makes more sense and could even help speed the process. While giving manufacturing a drawing often results in more questions than answers, so giving them CAD access makes this process smoother.

Switching gears (see what we did there?), we also see from the survey results that the other half of engineering leaders only receive useful feedback from a handful of folks on cross-functional teams.

This is not because these teams don’t have useful feedback to give. More often than not, it’s because engineering teams don’t have the right tools or the right process to involve the right cross-functional teams in the right files at the right time.

This doesn’t seem like a project-critical problem, so companies don’t prioritize this issue. However, this problem surfaces in myriad ways – namely, in late stage errors. But the solution is often a short-term band-aid. “Oh, this late stage change occurred because we didn’t get tooling’s buy-in on the drawing. Next time, get tooling’s buy-in on the drawing.”

This whack-a-mole method for solving late stage errors means companies only solve for the biggest, most immediate problem – and, the root cause issue never gets solved.

For Schaeffler, this became a company-wide priority to invest in improving business processes across the entire organization. Because they realized design review quality is a strong predictor of both product development speed and manufacturing efficiency, Schaeffler chose to focus on improving design reviews.

Schaeffler’s digitalization team saw three specific opportunities to improve their design reviews:

- First, they wanted to maximize the amount of valuable feedback and action items captured in reviews: "I've spent a lot of time in design reviews and I’ve seen how information can fall through the cracks,” explains R&D Business Analyst Lewis Bragdon.

- Second, Schaeffler saw an opportunity to simplify review management, driving speed and efficiency.

- Finally, the digitalization team wanted to give Schaeffler engineers an easy way to reference historical design decisions. They envisioned a system where any engineer could look up why a decision was made, with the context of the CAD version used to make that decision.

The important theme here is that Schaeffler, like many large engineering organizations, realizes how critical design reviews are across the business. These decisions don’t just affect the engineering team, they trickle through every cross-functional team that touches product development.

Understanding the engineering-supplier collaboration gap

We can see from the data that no engineering leader believes they get full supplier participation during design review.

We also see that this is the first group where some percentage of engineering leaders say they get zero design review participation from their supplier base.

Because of how manufacturing companies operate, this isn’t all that surprising. Typically, supply chain or procurement owns the supplier relationship. This means supply chain and procurement also own all communication. To get suppliers into design review, then, would mean involving supply chain and/or procurement in design review – which adds unnecessary complication.

The issue is: engineering leaders want suppliers to participate in design reviews.

Often, teams solicit supplier input too late in a pilot build, then there’s a critical design change, and so a “frozen” design has to go back to stage 1. These late stage errors are what cause 90% of companies to delay product launches.

So, engineering recognizes that supply input earlier during product development is essential.

But, the way companies structure teams means this input is too hard to solicit. To get a supplier into design review today looks like:

- Packaging up files in PLM

- Getting appropriate sign-offs from the PLM admin

- Having supply chain or procurement send the file package to the supplier

- Waiting for the supplier to add feedback

- Getting feedback form supply chain or procurement

So more often than not, engineering teams get supplier feedback when they can or when it’s absolutely essential.

Despite all this, it’s important to note that 65% of engineering leaders believe they get useful feedback from some or most of their suppliers.

This is just as important as the first point.

We have some portion of engineering leaders who get zero useful feedback from suppliers during design review and we have a significant percentage of engineering leaders who do get useful feedback from their supplier base. It stands to reason, then, that engineering leaders should be encouraging suppliers to provide as much useful feedback as possible during design review

Why?

Because now we know it’s possible. It’s possible to get useful feedback from suppliers during design review. Therefore, engineering teams should be looking to maximize this useful feedback as much as possible.

For Mainspring Energy, this initiative was clear. What they didn’t know was how.

Before finding a solution, most communication with suppliers was happening via email. Slide decks would be converted into PDFs and design input would be emailed back and forth. “It all ends up being a slow process,” recalled Kevin Walters, Director of Hardware Engineering.

“It also forced a lot of live meetings because it can be so hard to get the right screenshot that really gets the design intent across,” Walters continues.

“So then you’re getting 10 people in a conference room for an hour. You're going to have your doc up on the screen and you're going to try to load it up in SolidWorks. And with really big CAD models, that doesn’t always work smoothly or fast.”

Fed up with this process, Mainspring realized there was a big opportunity to speed up product development by streamlining their design review and engineering collaboration processes.

“This is a really deep cross-functional problem because it's not just mechanical engineers designing things, but we have other engineering teams that we're interfacing with — electrical, software, systems, controls — and then we also have our supply chain team and our suppliers,” explains Walters. “Those are all stakeholders in the design process.”

This is the mindset shift required for engineering teams and manufacturing companies: that every person who touches product development is also a stakeholder in the design process.

Once this happens, then engineering teams can feel more empowered to include suppliers in the design process and get more valuable feedback from a greater percentage of those suppliers.

When the people who matter most contribute the least

Every company believes it’s customer-centric. After all: no customers, no business.

Yet, when we examine the data here, the group with the lowest participation and the least amount of valuable feedback is: customers.

Let’s just summarize this so we can dig in:

- Only 6% of engineering leaders believe they receive useful feedback from most of their customers.

- 40% receive useful feedback from some customers.

- 45% receive useful feedback from one or two customers.

- 9% of engineering leaders say customers do not participate in design reviews at all.

So, the majority of engineering teams get useful feedback from 0-2 customers during design reviews.

Similar to interacting with suppliers, because customers are an external party, sharing data and soliciting feedback from them is often unnecessarily difficult. And the consequences of not including them are just as high as, if not higher than not soliciting their feedback during the design process.

Customers inform product development requirements to some extent – either fully (ETO, for example) or partially (market demands, OEM-to-supplier). Yet, companies solicit customer feedback far too late during product development. And often not at all, only soliciting feedback post NPI.

The consequences of this show up in poor OEM relationships, frequent ECNs, warranty claims and declining customer satisfaction.

For Ford Pro, they needed a better way to bring their converter partners earlier into product development. To deliver the best product to their commercial fleet customers, Ford Pro partners with a network of converters. These converters are a key part of Ford Pro’s reach and competitiveness, so ensuring Ford is the partner of choice for their converters is a critical priority.

In a recent project, MS-RT worked with Ford Pro, Ford manufacturing, and a third party supplier of custom wheels. With four different engineering teams weighing in on the design, finding a way to stay on the same page was essential.

Then on a more global level, communicating core design changes from Ford to the converters was also difficult.

For most teams, this level of communication requires more engineers, more emails, more project management and more work across the organization.

And this is why most engineering leaders respond this way when asked how many customers provide useful feedback during design reviews. It’s not only too difficult, they don’t have a way to do it.

How to get better feedback from more stakeholders during design review

The problem is clear: not enough stakeholder groups participate and provide useful feedback during design reviews. This problem leads to:

- 90% of companies delaying product launches

- 98% of companies delaying NPD project milestones

- 60% of late stage design errors that could have been prevented with better design reviews

The solution is what’s not as clear. For engineering leaders in this same survey, the majority answer is a better tool for design reviews. But, no one is sure what that tool exactly is, or even what it should exactly do.

The best engineering teams in the world are discovering this answer.

It’s a Design Engagement System.

About the survey

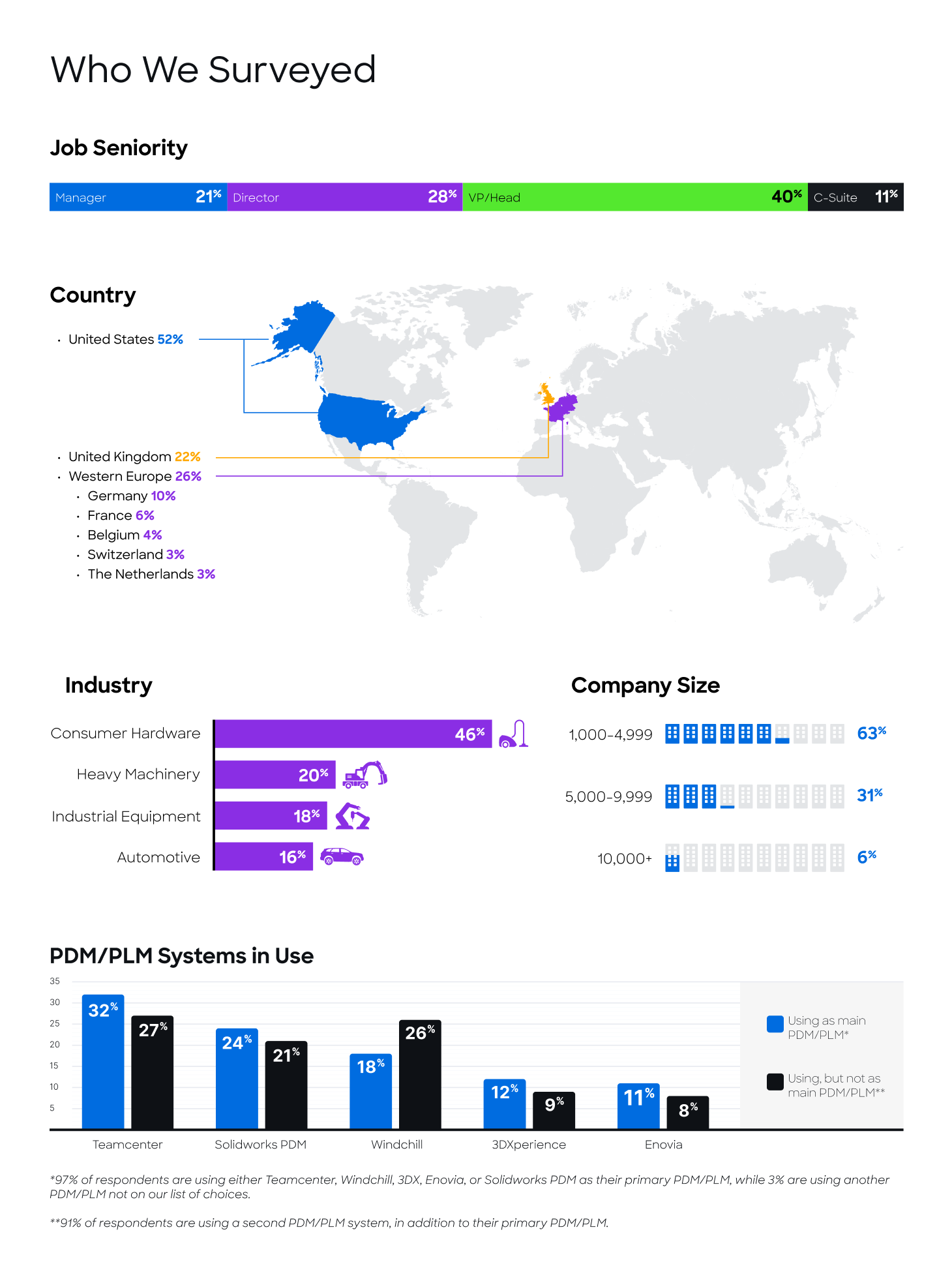

To get greater insight into the state of complex product development processes, we commissioned a survey of 250 full-time employees, 50% of which are Engineering Managers or Directors, and 50% of which are VPs or C Level Executives.

Respondents work in the manufacturing industry, specifically in industrial equipment, heavy machinery, automotive, and consumer hardware, and are split across the US, the UK, and Western Europe.

All respondents work at companies with 1,000+ employees that have already invested in a PDM or PLM system.

This report was administered online by Global Surveyz Research, a global research firm. The respondents were recruited through a global B2B research panel, invited via email to complete the survey, with all responses collected during October 2023. The average amount of time spent on the survey was 5 minutes and 44 seconds. The answers to the majority of the non-numerical questions were randomized, in order to prevent order bias in the answers.

This article is part of the CoLab Research Reports series, where we publish findings from both engineering leader surveys and aggregated, anonymized CoLab data.

Quantifying the impact of design review methods on NPD