The most common design review mistakes

In the product development process, design reviews should be moments of clarity: when unseen issues are revealed, risks are mitigated, experts from all areas collaborate. The result? A coordinated manufacturing team emerges with confidence in the path ahead. That has to be the goal, every time out.

What are they in reality? They are seen as a step in a larger process that needs to be checked off to push a product down the pipeline. At their worst, all sorts of problems can happen during design review: confusion, stress, mis-alignment, miscommunication, which all lead to late in-cycle changes that increase cost.

At CoLab, we’ve been focusing on design review for almost a decade now. This article explores the most common problems that we have seen that plague design reviews and why they persist, and what gains can be had by doing them better.

Here’s one of our clients explaining the issues they have had with design review, in their own words:

"I've spent a lot of time in design reviews and I know the kinds of headaches that can happen in design reviews, how information can fall through the cracks. Time is a really big issue. Managing everything: All of the information, all of the tasks that have to be done. All of the action items, who is responsible: the deadlines, the reasons that design decisions were made. You can look at the confusion that happens when you don't know which iterations of CAD files were considered or when a specific design decision was made – especially when the only documentation you have was in emails or Teams chats or maybe just a verbal discussion in a conference room somewhere. And then you have files that are in Excel formats. Everything is decentralized."

R&D Business Analyst Lewis Bragdon of Schaeffler from case study “Schaeffler balances design quality and efficiency, with help from CoLab and PTC”

We don’t even consider that an exhaustive list of what can go wrong with design reviews!

To make design reviews work effectively — which means saving companies money and speeding up development — we first need to understand what usually goes wrong with them.

At CoLab we believe that functioning at their best, design reviews are a linchpin to accelerate a company’s entire product lifecycle so that better products are made, faster.

Recurring problems we see most teams face in design review:

- Undefined purpose and drifting conversations

- Fragmented documentation: Not all feedback being considered

- Suppliers not consulted: They have specialized insight

- No centralized, accessible content: Everyone benefits seeing the same thing in real time

- Compliance treated as the goal rather than the context

- No lessons actually learned. The same issues return, despite best efforts.

By the end, we hope you don’t see your company in these points at all. But if you do, we hope you’ll realize you’re not alone and that there are ways to improve on all of these situations.

Undefined purpose: Results without traceability

Many review meetings open with a walkthrough of models, diagrams, or slide decks, where participants have an unclear understanding of the purpose of the review. Goals can vary:

- Is the goal to validate manufacturability or align on DFM?

- To align on user experience?

- To surface compliance risks?

- To show regulatory requirements have been achieved?

- To ensure all relevant expertise has been captured?

- To consider alternate design options?

There are dozens of other reasons why an engineer could want to do a design review. What we’re flagging is that the purpose cannot be taken for granted or insufficient or inaccurate information is going to appear.

“What are the decisions that we need to make as a result of this design review?” is a question that must be answered at the outset, says Tyler Vizek, Senior Customer Success Manager at CoLab and a former Mechanical Engineer at Northrop Grumman. “This is so that all your reviewers come in prepared, knowing what the ideal outcome is and how we work together to get there.”

Another issue that can happen is “bike shedding.” Unless design review is driven with purpose. That’s a term for when companies focus on something more trivial than the main build, like a bike shed, as opposed to concentrating on the overall building, explains Andy Clarke, Senior Customer Success Manager at CoLab, who worked for more than a decade at companies like aPriori Technologies and Schlumberger as an engineer.

Clarke flags that the “Abilene effect” is another common issue, where people come to a meeting where everyone leaves without saying the one thing they are thinking: “This won’t actually work.” Meanwhile, the process moves along. This can have disastrous consequences: NASA eventually revealed that some 31 engineers were aware of O-ring issues when the spaceship Challenger exploded in 1986. Seven people died in that blast. “For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled,” physicist Richard Feynman famously wrote in the official report on the Challenger disaster.

“For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled,”

- physicist Richard Feynman

The lesson is clear. Have a clearly stated purpose for your design review session and find ways to encourage people to speak their minds. Otherwise, you don’t know what you’re trying to achieve and won’t ever know if you’ve built a design that works until it’s too late.

Case study: Rework at Raptor Aerospace leads to immediate $2M in cost savings

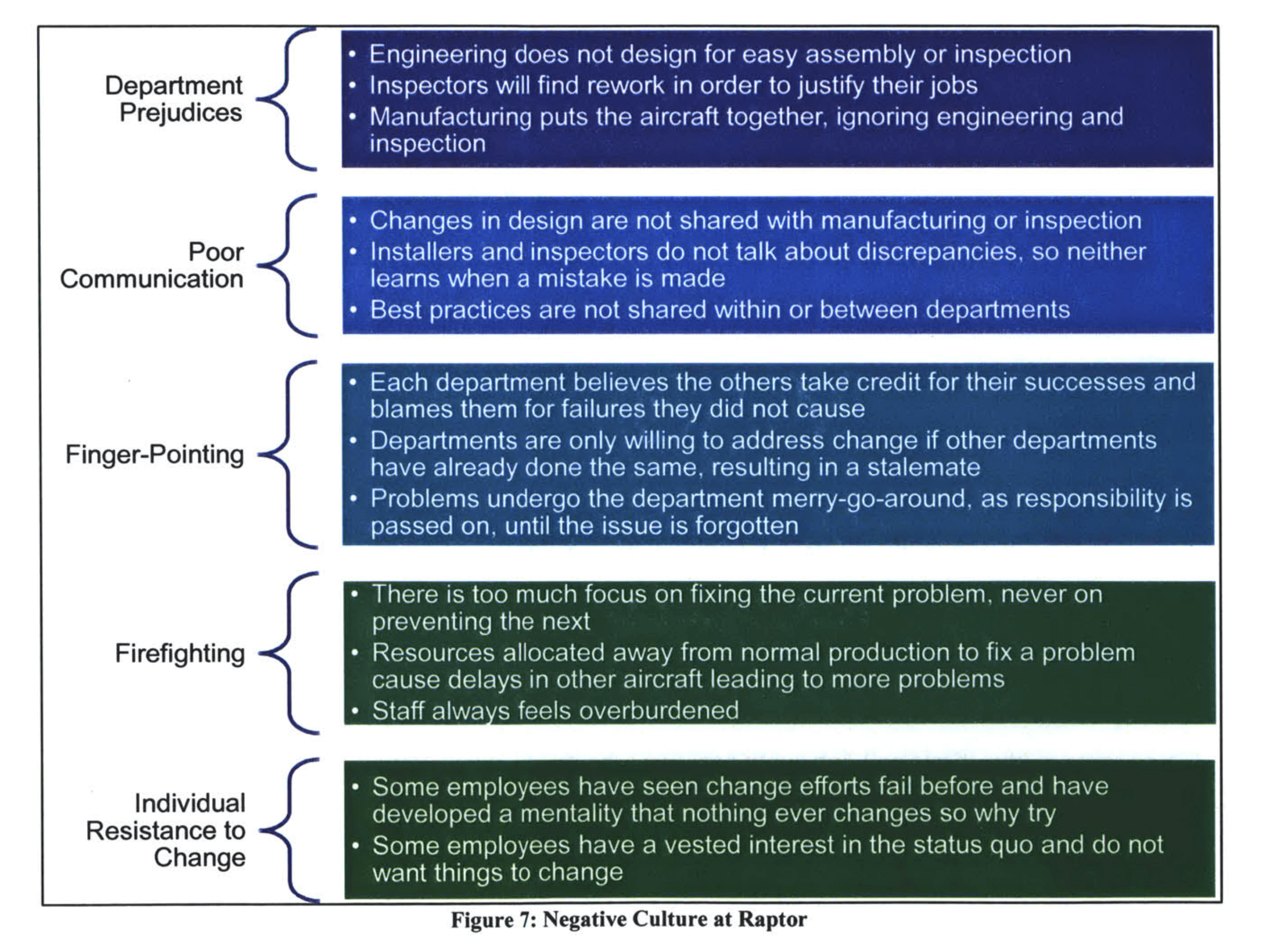

An MIT thesis identifies that Raptor, an aerospace manufacturer, faced significant annual losses (over $50 million US) that were tied to rework stemming from deviations from drawings. Over a 6.5-month improvement project, teams used inspector reports and root cause analysis to identify the most frequent rework causes. The solution was to introduce more rigorous checks earlier in the assembly process. Most importantly, they aligned teams on expectations for design vs. manufacturing handoff and automated tracking of deviations. What was crucial was to establish the purpose of the design period.

The result: over US$2 million in annualized savings from reduced rework. The accompanying chart points out all the issues that arose. Beyond functional problems, cultural problems were flourishing (at CoLab we often find they go hand in hand). They include competitive siloed departments, as well as a refusal to address persistent and consistent problems. Firefighting became normalized to the point that problem prevention fell away in the process.

The lesson? Make it clear what the goals are to get everyone on the same page. You can minimize silos and you’ll save money down the line.

Fragmented documentation: Did you write that down?

I'm going to say where 90 to 95% of people fall on their face is the last two steps: capturing information and then actioning it in the future.

Lucas Walker, Solutions Engineer, CoLab Software

Most design teams keep notes in some fashion, as a way of tracking issues.

If the issues are resolved, many companies even maintain large “lessons learned” files to apply them to future programs.

Issue tracking is often cited as a haphazard process. Notes are scattered, hidden in email threads, slide comments, or handwritten notebooks. Some companies use PDF-exchange editors, which does capture the feedback in a format everyone can see. Others have considered software for tracking, but abandon it because it’s seen as too difficult to learn and adopt.

It’s easy to see why this happens. Design intent is difficult to convey when flagging an issue, because it requires a great deal of context. Some CAD viewers have markup tools that theoretically work for this, but they document individual issues. A markup file for every issue creates chaos quickly.

This is often why PowerPoint has had such staying power. Each issue gets a slide. But that creates admin work and a 2D PowerPoint cannot convey what 3D can. So the feedback comes on an ungainly replica. Change the CAD and the deck is immediately out of date.

Accessing CAD can be a chore. Not everyone involved in trying to do a design review will have access. The logistics of lugging in a desktop computer powerful to run CAD into a meeting is a persistent hassle at some companies that have underfunded IT departments (we know it still happens!). Every issue like this is just another difficulty that the design review process must overcome.

Flagged issues each need to be tracked and resolved - although they happen through emails or calls or notes or even conversations in a hallway (CoLab makes this possible with feedback pinned to drawings or CAD). Meanwhile the actual CAD is changing so you don’t even know if the changes you’re making are for the latest revision anymore. Email chains extend so that they become nonsensical. It’s a recipe for chaos, even if done well–and in particular when you realize it’s entirely possible to have 4,000 design issues for a complex assembly.

As for lessons learned? A lack of centralized, accessible content creates lessons that are never actually realized. Information stored in senior engineer’s heads is lost once they retire. The result is insights meant to prevent repetition are forgotten and over time the same mistakes recur. Time is wasted on issues that have been flagged time and time again but never fixed.

- These issues can be quantified. We did a poll of engineers across industries and found that 43 per cent of design review feedback is lost. That leads to errors being fixed later on: 90% of companies delay product launches due to late stage design issues.

Case study: No interest in looking back

Lucas Walker is a Solutions Engineer at Colab who worked as a Lead Manufacturing Engineer in his decade of experience in the field. But that experience is just in his brain now. The biggest issue that he continually saw was that knowledge wasn’t passed on.

“I made a retro document for one project and nobody ever looked at it. I tried, everybody just didn't show up. We had never done retros. And I think they're like one of the most powerful parts of projects in general, let alone design. Because there's no other way to learn.

“I had a lot of historical and contextual knowledge in my head in my last two roles that didn't live anywhere else. And so, we'd get into a design review and as the manufacturing lead I'd say, `Oh, we've actually made that mistake before. We can't be doing that.’ The design engineers would be like, `What?’

In some cases, Walker explains, the engineers had done the previous design, meaning they had made the exact same mistake twice.

That might seem like it’s a skill issue. But it’s not, Walker insists. It’s actually a product of a skilled person working hard in a system where they are set up to fail.

“It's no fault of the individuals. They're just pushing so much volume through their process that at some point you forget. They might even see it and be like, "Ah, something feels familiar," but they don't action it.”

Suppliers are often invited into design reviews only at the end when their influence is marginal. Late involvement triggers delays and cost overruns because of inflexible designs.

There are often good reasons for this. Distributed teams are a key aspect of design review today. Modern products are built all over the world, with stakeholders and experts to match. If design review is done in a meeting, it can literally be impossible to invite people if they are halfway across the world and the time isn’t conducive to them attending. However, the tradeoff is that you lose out on crucial expertise that could actually improve the product. Typically, the feedback either doesn’t come or when it does, it’s too late. Or it takes too much time. Going back and forth with a supplier in China if you’re in North America can add weeks to development.

Design review was originally created so that engineers could talk to each other. But more collaboration is required. Creating a system built for the modern design process that takes into account international collaboration - was a key factor in developing CoLab’s software, which allows suppliers to comment on your existing CAD.

Case Study: Early supplier involvement in electronics & automotive Industries

A Swedish study examined a supplier of capital goods instead of looking at the issue more typically from a manufacturer’s point of view. It found that when suppliers are involved late, they face information gaps, unclear requirements, and misalignment with OEM expectations, all of which lead to increased rework, greater costs, and delays. The study highlights gaps that occur between suppliers and manufacturers by explaining they come at the same task with completely different perspectives unless aligned. These are gaps that can be closed in a good design process: “the customer and supplier have different views on the complexity of the product design task and therefore have different opinions about the necessity of information exchange. It is also conceivable that the customer does not understand what information is relevant to the supplier since it seems obvious for the customer.”

SOURCE: “Challenges with Supplier Involvement in Product Development: A Supplier’s Perspective,” by Flankegård, Johansson, Granlund, among others. Cambridge University Press & Assessment

Across all these problems, a single issue stands out: many reviews proceed without clear intention. Key elements often missing:

- What kind of feedback is needed now (usability? manufacturability? compliance? cost?)

- Who must participate (engineers, suppliers, users)

- How decisions will be made and enforced (action items, ownership, validation)

The main issues created?

- Time is wasted waiting for feedback, as people struggle on what feedback to give, because they don’t understand the intent. Design reviews can take weeks or months instead of days.

- Downstream issues keep popping up because the design review wasn’t done properly. Changes later cost more, simple as that.

How design leaders can reset the process

Ineffective reviews cost time, money, and confidence. But there are clear, proven ways to fix them. Drawing from the case studies above, design leaders can reset their review process by focusing on fundamentals:

- Define Review Objectives at Each Stage

- Capture Feedback Consciously

- Bring Suppliers and Key Stakeholders In Early

- Use Compliance as a Framework

- Create a Method for Knowledge to Remain Within the Company

These were many of the principles behind CoLab’s software development. This was the goal: To make a product that would help engineers and manufacturers collaborate and retain information.

Turning design reviews into strategic assets

Design review problems are common: drifting conversations, weak documentation, late stakeholders. But when organizations build intentionality into review processes, they capture knowledge and encourage real collaboration.

For design leaders seeking advantage, the opportunity is clear: transform design reviews from a procedural burden into a strategic tool. The organizations that do will see fewer delays, less rework, higher product quality, and more confident teams.

Want to read more? Learn about Boom SuperSonic, which figured out how to build a modern supersonic airplane by changing almost everything we know about the design and manufacturing process.